This #WITMonth, it was the translator who attracted me to my featured title. I often find this is the case: now that I’m relatively well versed in how books come into English, there are certain translators’ names that predispose me to try stories. Because I admire other projects they’ve done or know them to be particularly committed to championing interesting voices, I regard their involvement with a book as a sign that something is worth investigating.

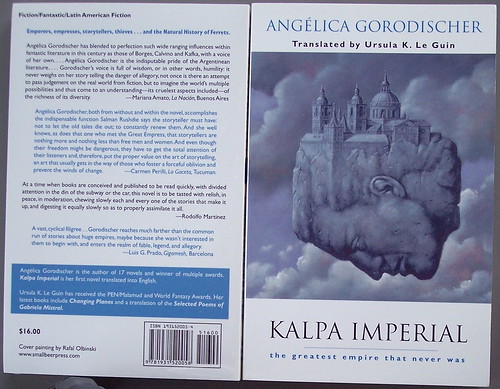

In the case of Angélica Gorodischer’s Kalpa Imperial, originally published in Spanish in 1983, it wasn’t the translator’s other translations but her novels that piqued my interest. Despite not being particularly keen on sci-fi (although I’m warming up to it in my fifth decade), I’m a big fan of the work of the late Ursula K. Le Guin. If you haven’t read her, you’re in for a treat.

Along with her novels, poetry, short fiction, criticism and books for children, Le Guin’s website lists four translations in her bibliography. Kalpa Imperial: The Greatest Empire that Never Was is one of these.

As its subtitle suggests, the book charts the history of an imaginary empire. It does so through multiple voices, bringing alive the idiosyncrasies, cruelties, obsessions and triumphs of a host of the personages who have shaped and been shaped by this history.

Many of these figures are marvellous creations. Take the dealer in curiosities who buys a boy who can dance in an era when dancing has been forgotten. Or the urchin who shrugs off her abusers and rises to be empress. And there are numerous sadists in the mix too – many of them military men who delight in pursuing their proclivities in the professional arena.

The prose is similarly inventive and startling. Lyricism jostles with surprise on every page. There is also plenty of humour.

Lists in novels are frequently a bugbear of mine: I find them wearing and am often tempted to skip them. But Gorodischer and Le Guin’s lists engrossed me – masterclasses in rhythm and the subversion of expectations.

There is subversion at the structural level too. Sometimes events are narrated several times by different voices – fishermen, passersby, servants and a dedicated storyteller. Indeed, along with the empire itself, the figure of the storyteller is the only consistent presence in the book. Most discussion of the novel I’ve seen declares that there are multiple storytellers involved in it. This wasn’t clear to me – I read the storyteller as being a single voice. But if you know different, please tell me!

Certainly, the tone of the storyteller is varied. At times fawning and affectionate, the narrator can also be downright rude to the reader – ‘if you could imagine anything you wouldn’t have come here to listen to stories and whine like silly old women if the storyteller leaves out one single detail.’

What remains consistent, however, is the book’s excavation of the mechanics and purpose of storytelling. ‘I’m the one who can tell you what really happened, because it’s the storyteller’s job to speak the truth even when the truth lacks the brilliance of invention and has only that other beauty which stupid people call mean and base,’ the narrator declares at one point. And at another: ‘a storyteller is something more than a man who recounts things for the pleasure and instruction of the crowd[…] a storyteller obeys certain rules and accepts certain ways of living that aren’t laid out in any treatise but are as important or more important than the words he uses to make his sentences[…] no storyteller ever bows down to power’.

There is a clarity to the prose and to the insights the book presents into its characters’ motivations that reminded my of Le Guin’s other writing.

This got me thinking anew about the influence of readers and translators on stories. It’s something that’s been on my mind lately as I’ve been receiving feedback from beta readers on the manuscript of my forthcoming book, Relearning to Read: Adventures in Not-Knowing (preorder your signed collectors’-edition copy now!). The brilliant insights and responses I’ve had from these first readers have been invaluable in helping me finetune the book, and they have developed my understanding of it too. Relearning to Read now carries their influence and is the stronger for it.

Translators, of course, aren’t simply readers providing feedback that a writer may respond to or ignore. They rewrite a book in their own words. But this rewriting is in response to reading. It can’t help but meld their own talents and perspectives with the strengths and weaknesses of the primary work. There is an inevitable hybridity to the end result.

Of course, part of what attracted Le Guin to the project of translating Kalpa Imperial may have been the sense of a synergy between her work and Gorodischer’s. Unlike many translators, Le Guin had the luxury of picking and choosing the books she worked on. Translation wasn’t her primary career.

Still, reading her rendering of this Argentinian sci-fi/fantasy classic, I can’t help but wonder if translation itself doesn’t have something of the fantastical or speculative about it: a processes that fuses the capabilities of two minds. It sounds like something Le Guin herself might have envisioned in one of her novels: a revolutionary technology that enables the magnification of creativity, multiplying the powers of those involved. In that sense, when a book is the product of two writers working at the top of their game, as the English version of Kalpa Imperial seems to be, might translations offer a supercharged reading experience, a kind of literature squared?

Kalpa Imperial: The Greatest Empire That Never Was by Angélica Gorodischer, translated from the Spanish by Ursula K. Le Guin (Small Beer Press, 2013)

Picture: ‘kalpa imperial’ by Dr Umm on flickr.com

Source: A year of reading the world