Book publicists are a curious breed. Although I rarely accept proofs and buy almost all the books I feature on this blog, I frequently receive emails from people promoting titles that will clearly be of no interest to me. Mainstream books by British and American writers. Business books. Academic books on subjects outside my area of expertise. As I delete these emails, I wonder if the people who send them see their job primarily as a numbers game: if they simply scattergun enough emails out into the universe, someone is sure to take the bait.

But every so often I encounter a book publicist who thinks carefully about my interests and sends me a suggestion that hits the nail on the head. These people can be gamechangers.

The fact that I do a Book of the month post on this blog is down to such a publicist. Back in 2014, Daniela Petracco at Europa Editions contacted me about an as-then little-known Italian author. I explained I was no longer doing book reviews here, but she wouldn’t take no for an answer. She didn’t care. She had to send me this novel, regardless. She loved it and she was sure I would too.

Reluctantly, I accepted a copy, was blown away by what I read and started my Book of the month slot in order to be able to tell people about it. And the novel? My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein.

This month, I had a similar experience. In response to my call for books published no later than 2020 that I might feature in my year of reading nothing new, I had an email from Daniel Li, working on behalf of Sinoist Books. He sent me three suggestions that he thought might fit the bill (which immediately made me warm to him, as this was a number of books I could reasonably check out, rather than an endless list of possibilities that would require several hours to unpick). Of these, Jia Pingwa’s Broken Wings, translated by Nicky Harman, caught my eye.

Described as a thriller, the novel tells the story of Butterfly, a young woman kidnapped from the city and taken to a rural village to be sold as a wife to one of the many men left single because of the gender imbalance resulting from China’s one-child policy and rapid urban migration. It opens with her scratching her 178th mark to record the days of her imprisonment on the wall of the cave in which she is held, and centres around the question of whether she will ever escape and find her way back to the life for which she pines.

But there the similarities to a thriller end. In fact they end even before the opening page, because in his foreword, Jia pretty much gives away the plot: he reveals that the novel grew out of a story he heard from an old man from his village about his daughter who was kidnapped and rescued, and who then, in the face of unbearable media attention, eventually returned to live with her kidnappers.*

Instead of delivering a gripping story (or instead of primarily doing that), this novel offers something even more engrossing: entering into and inhabiting the unimaginable, and making it feel personal, real. Jia puts it like this:

‘When I was young, death was just a word, a concept, a philosophical question, about which we had enthusiastic discussions that we didn’t take too seriously, but after I turned fifty, friends and family began to die off one after another, until finally my mother and father died. After that I began to develop a fear of death, albeit an unspoken one. In the same way, when a short while ago cases of trafficking of women and children began to appear in the media, it felt as remote from my own life as if I was reading a foreign novel about the slave trade. But after I had heard what happened to the daughter of my village neighbour, it all became more personal.’

In order to communicate this shift, Jia enters into Butterfly’s experience to an astonishing degree. He starts with the hardships of life on the unforgiving loess plateau, where people scratch a living trying to dig for rare nonesuch flowers and growing blood onions. The specificity of the detail is extraordinary. ‘What is there to see?’ the neighbour exclaimed when Jia asked if he had been to see his daughter. Jia shows us: the millstone with its runner stone worn to half the thickness of the bed stone over years of use; the rim of the well, scored with grooves; the gourds withering on a frame near the cave entrance.

Although spare to start with – reflecting, perhaps, Butterfly’s numbness – the language flowers over the course of the novel, as she adapts to life in the village. We start to see the beauty in rituals that at first seemed crude and beneath notice. As the prose takes trouble over recording the details of how to make a good corn pudding, we see Butterfly learning to value the world around her differently, adjusting to her new reality. At times the writing is strikingly lyrical and almost painful in its poignancy:

‘At noon, I gazed at the hills and gullies and knolls far away. Distance seemed to soften them so they looked like watery billows. I longed to escape from this ocean and climb back on dry land again. But when the sun set and it turned chilly and the light left the strip, the sea suddenly died, and I was left like a stranded fish.’

But it is Jia’s presentation of female experience, rendered through Harman’s arresting choices, that is most impressive. The description of her eventual violation by her so-called husband, Bright, and the physical trials of pregnancy are exceptionally well handled. And the portrayal of labour and birth are quite astonishing – up there with Eva Baltasar’s descriptions in Boulder, translated by Julia Sanches.

There are challenges for the anglophone reader. Oddly though, these do not concern the cultural differences you might expect – although the world Jia depicts operates according to strikingly different values, the humanity in his writing makes it relatable. Instead, it is technical choices concerning pacing and what descriptive information to include that occasionally prove taxing. Several times I found myself wrongfooted by not knowing whether a character was present or had moved to a place or performed an action, when a writer working in another tradition would have told me.

This was interesting, though, rather than off-putting – an insight into the things I take for granted and the supports I am used to expecting when I read. And a reminder that the technical and stylistic mores that we tend to regard as markers of good or bad writing in the anglophone tradition are more malleable and subjective than we might think.

Because the writing in Broken Wings is not simply good. It is marvellous. Playful, expansive, precise, moving and surprising, it sweeps us into another world, transforming this sad story into something almost sacred. Jia and Harman put it best, again in the foreword:

‘A novel takes on a life of its own, it is both under my control and escapes my control. I originally planned it purely a lament by Butterfly, but as I wrote, other elements appeared: her baby grows in her belly day by day, the days pass and her baby becomes Rabbit, Butterfly’s sufferings increase, and she becomes as pitiable a figure as Auntie Spotty-Face and Rice. The birth of a novel is like the clay figure shaped in the image of a divinity by a sculptor in a temple; once it is finished, the sculptor kneels to worship it because the clay figure has become divine.’

Broken Wings by Jia Pingwa, translated from the Chinese by Nicky Harman (Sinoist Books, 2020)

* The publisher informs me that this foreword is an afterword in most editions, including the original Chinese, but it appears as a foreword in some ebook editions. Because of the sensitive nature of the subject matter, they encourage readers to read it first (although my usual advice would be to leave all extraneous text until after you have read the primary text).

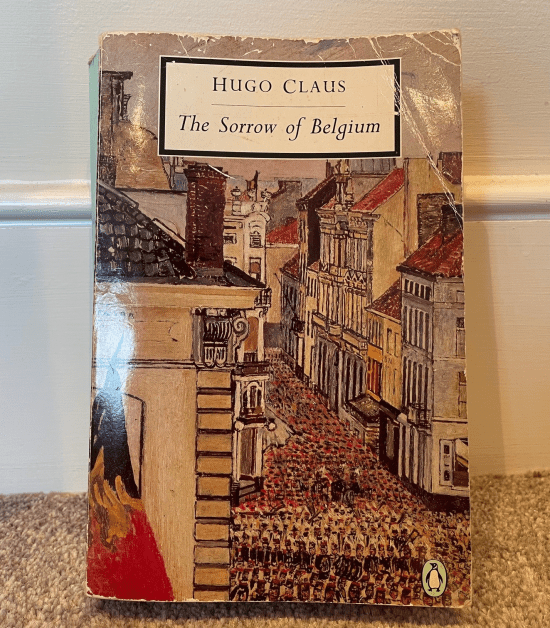

Picture: I, Till Niermann, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: A year of reading the world