This book was one of two sent to me by Colin. He was going on a trip to Kosovo and volunteered to go to some bookshops on my behalf to see what Kosovan booksellers would choose for me as standout books from their nation.

Kosovo wasn’t included in my original year of reading the world. Although it’s recognised by more than 110 countries, it isn’t officially UN-recognised. As such, it’s one of the many nations that fell under the ‘Rest of the World‘ banner, which ended up being represented by Kurdistan that year.

I was intrigued to see what Colin what find. He sent me an email from Prishtina, where he had had a great conversation with a bookseller at Libraria Dukagjini. She recommended three titles that had been translated into English: the international hit My Cat Yugoslavia by Pajtim Statovci, who writes in Finnish, translated by David Hackston; Night Trails by Mustafe Ismaili, translated by the author; and Glimmer of Hope, Glimmer of Flame by Ag Apolloni, translated by Robert Wilton and published by Elbow Books. She also mentioned an untranslated novel, Genjeshtars te vegjel by Fatos Kongoli (which translates Google translates as ‘Little Liars’).

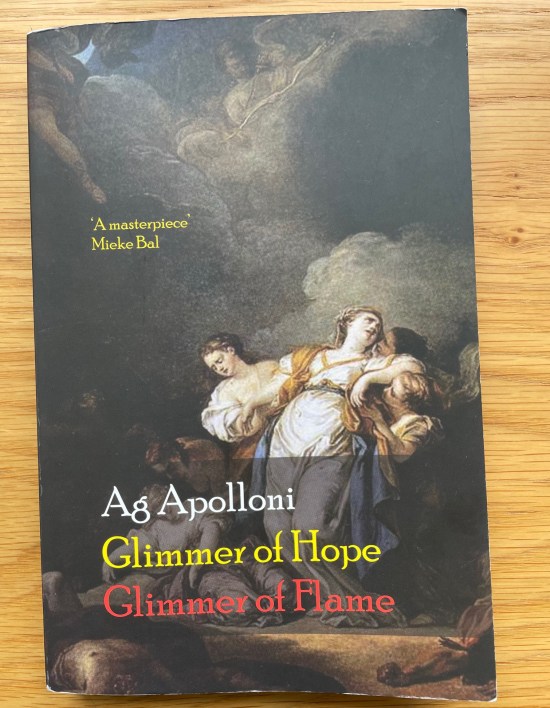

I have MCY, but the other two translations intrigued me. Colin posted these to me, persevering when the British customs returned the books first time round. The Ag Apollini in particular caught my eye. ‘A masterpiece,’ proclaimed Mieke Bal on the cover and it had been named as Kosovo’s 2020 novel of the year. I decided I’d better see what all the fuss was about.

Apolloni calls this book a ‘documentary novel’ and I can see what he means. Built around a real-life research trip he made with academic Dritan Dragusha and film director Gazmend Bajri, the narrative records his responses to the stories of two women whose families disappeared during the Kosovo War. One, Ferdonija, spends her life waiting, still setting the table twenty years later in the hope her four sons will return; the other, Pashka, burnt herself to death when the remains of two of her children were returned.

Yet, in many ways, this book is more essay than documentary: it brings in Apolloni’s thinking on Greek tragedy and weaves together literary and cultural references from throughout human history to cast the hideous events of the recent past in a timeless, mythic light. Reflecting on the fact that of the more than 100 plays Aeschylus is known to have written only a handful survive, it explores what loss on every level means and how it shapes the human condition.

At the centre of the book is an intellectual challenge: how do you tell a story about someone who has no future, whose life is in the past? Apolloni puts it like this: ‘how can you write something about someone who just sits and laments their own fate?’ Stories are surely action and agency, after all? Protagonists do things.

Aeschylus provides the answer: the lost play, Niobe, surely did just that, recording the suffering of the bereaved mother at the heart of it, taking the audience into the centre of her pain. Apolloni sets out to achieve something similar.

And he succeeds. This is no cold, academic exercise. Feeling is everywhere in this book, both in the raw and extraordinary portrayal of Pashka and Ferdonija, but also in the other stories that touch theirs, many of which are realised in no more than a sentence or two.

A particularly moving section involves a visit from a high-profile Holocaust survivor, who comes to meet the war’s victims. ‘What I know is that I must be here at least,’ he tells a woman. ‘I must be. I cannot suffer in your place, but I have to be present at your suffering. That’s all I can do.’

Yet, in being present in such a way, he is himself a sort of timeless figure – ‘like the high priest of Shiloh, determined in his compassion to shelter all of the children and raise them in the tabernacle’. By being intensely part of specific, extreme experience, he assumes a sort universality.

This is a key theme of the book: timelessness is made out of intense nowness, out of raw, compacted pain. ‘Tragic myths are created by great shocks. In the direst cases, we are myths recycled.’

So it is that the contemporary details of Ferdonija’s static existence speak beyond their moment. The descriptions of the photographers posing her and staging her home so as to present her grief as they see fit reveal themselves to be part of the changeless human condition. The feelings this evokes resonate with Niobe, with Electra, with Antigone – with all those mythic female figures who lamented and felt the weight of others’ eyes upon them.

The universality of these feelings stretches not only back through time but outwards across political boundaries. In the face of such a story, all people, regardless of their heritage and allegiances, cannot help but respond. So it is that when Gazmend Bajri screens his film, people on all sides of the conflict respond to the suffering: ‘Pain is human, not national. This has nothing whatever to do with nationalism, and so the audience suffered along with the actor.’

Of course, reading this book now, in another time of great suffering, adds another layer. When many in other parts of the world – in Palestine, in Sudan, in Ukraine, to name but a few – are experiencing similar horrors on a comparable scale, this story feels particularly telling. For many, the thought of reading it might seem too much – the last thing you want when we are already bombarded with so much misery.

Yet this is precisely what makes Glimmer of Hope, Glimmer of Flame uplifting. In the face of so much suffering it is easy to feel helpless and overwhelmed. Storytelling – when it is as honest, humane and insightful as this – gives us a way to get alongside these experiences, to be present. By giving shape to sorrow, stories allow us to commune with it: ‘Gazi films Ferdonija so that we too may feel her tragedy; he knows that this is how you kindle cartharsis in the spectator, participating in the suffering of the main character, so that passio becomes compassio.’

There may not be anything we can do in the face of these horrors, Apolloni shows us, but there is a way we can be.

Glimmer of Hope, Glimmer of Flame: a documentary novel by Ag Apolloni, translated from the Albanian by Robert Wilton (Elbow Books, 2023)

Source: A year of reading the world