Fancy Ice Is Art in Your Glass

This article is adapted from the October 5, 2024, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

Where I live in California, it’s been an unseasonably warm fall. While cafés and grocery stores are going full-speed ahead with all things autumn, no one I know is running to get a pumpkin spice latte yet, considering the 100-degree plus temperatures. Instead, we’re all still craving anything cold and iced.

The other day, I saw my first at-home pebble ice machine, and I was filled with a brief longing to buy one for myself so that I could enjoy textured, crunchy ice whenever I wanted.

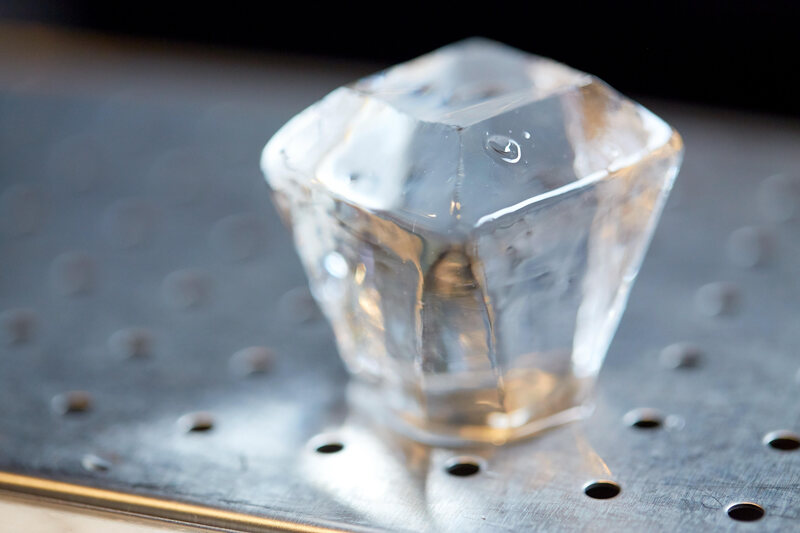

Alas, all of my ice comes from plastic trays in the freezer. But I’m fascinated by the growing number of people who treat ice as an art. Instead of cloudy, rectangular cubes, some bartenders hand-carve sparkling frozen forms out of perfectly clear ice. Others use special molds, edible flowers, juices, and fruit to create ice that adds flavor and texture to a drink, as well as cooling it down.

Focusing so much effort on ephemeral ice might seem impractical. Yet people often fixate on the perfect liquors, the perfect glassware, and the perfect drink-making technique. Ice is an essential part of many beverages, so this week, we’re finding out more about this fascinating frozen art.

Cool History

Before refrigeration, ice was a flex. Around the world, there are records of the wealthy and powerful sending their servants up high mountains to bring back snow for drinks and desserts.

Even those without convenient snowy mountains nearby could enjoy cold treats on hot days by constructing insulated buildings and stocking them with winter ice cut from bodies of water nearby. But this depended on having a cold enough climate during the winter.

In the 19th century, fast ships and railroads could carry ice around the world. The United States began shipping ice from its lakes to far-flung locales like the Caribbean and England. But Americans kept plenty of that ice for themselves, adding it to trendy new mixed drinks called cocktails.

In the 20th century, home freezers made ice more accessible than ever before. But, until recently, people have stuck to cloudy white cubes to cool down their drinks.

Ice Gets Hot

Over the past few years, I’ve seen “ice restock” videos appear across my social media feeds. These consist of influencers showing off floppy silicone ice molds filled with colorful frozen liquids and fruits, and the process of popping out aesthetically-pleasing ice into freezer drawers.

Comments range from admiring to skeptical, but there’s no denying that the sounds of ice cubes (there’s often an #asmr tag) and the colors of the ice are appealing. Creations like pink, cherry blossom–shaped ice and ice frozen into rose shapes and sprinkled with dried petals almost seem too pretty to submerge in a drink.

Of similar interest are videos of bartenders, especially from Japan, painstakingly carving clear ice into spheres or diamonds. But why would a bartender want to take time out from a shift to hand-carve a piece of ice? There’s numerous explanations: certain shapes, such as spheres, melt slower and dilute a drink less, and a good number of small Japanese bars buy their ice in huge chunks that need to be broken down anyway.

The Quest for Clear Ice

These factoids come from Camper English, the author of The Ice Book: Cool Cubes, Clear Spheres, and Other Chill Cocktail Crafts. Over the last 15 years, English has made a name for himself as the internet’s ice guru, a reputation established by a long-ago quest to create clear ice at home.

It all started with a bit of mythbusting, he explains. He attended a cocktail conference where a panel touched on the subject of making clear ice. “So I decided to test the theories that people were suggesting, methodically, at home,” he says. For example, many people think that freezing boiling water will result in clear ice. English tried it. It didn’t work. “It’s more of an urban legend than anything else,” he says.

So he set out to develop a standardized process. In his book, English describes freezing different kinds of water in different containers, but all his ice ended up cloudy-white in the center. It took a lot of ice and observation before he noticed that the outer edges of his ice cubes stayed clear. On December 28, 2009, he posted this finding: freezing water in an insulated container without a top would result in a piece of clear ice with a cloudy layer at the bottom that could be chipped off.

This, he explains to me over the phone, is known as directional freezing. The last part of water to freeze will end up cloudy from trapped air and impurities. Usually, that’s the very center of an ice cube, but using an insulated container without a lid “only freezes from one direction, which is the top down towards the bottom,” he says. You can also get see-through ice from not allowing a cube to freeze solid, keeping the center liquid.

Both home and professional bartenders absorbed English’s findings, and there’s now an industry creating tools to make ever-more fanciful clear ice at home. “I’m glad that it’s still going all these years later,” says English. He hasn’t gotten tired of ice, either. “I have fun with my reputation as an ice weirdo,” he says. “I rarely keep food in my freezer if I can avoid it because I’ve always got a few ice projects happening in there.”

“You don’t think of people who knit a lot as being obsessive or weirdos. My hobby is making ice cubes that are really good,” English laughs. “So save your judgment, people.”

English has noticed an uptick in the number of people doing ice projects the last few years. “Initially, the process that I shared was known among bartenders, but it really took off only during the pandemic when a lot more people were trying to make good-looking drinks at home,” he says.

In his book, English demonstrates not only how to make clear ice, but also how to suspend flowers and fruit inside cubes, make frozen punch bowls, and how to create frozen spheres to hold cocktails. Ice, he says, can do much more than simply cool down a drink, and even a single cube of clear or colorful ice can make a cocktail feel special.

“I often use the analogy of drinking fine champagne out of a Styrofoam cup while sitting in a ditch, as opposed to drinking the same champagne from a crystal flute in a fine-dining cocktail bar,” English says. “It’s the same champagne, but the experience is elevated with a better visual environment.”

Recent Posts

TTArtisan Brings Its $200 75mm f/2 AF Prime to L-Mount

TTArtisan's AF 75mm f/2 portrait prime lens, previously available only for E-mount and Z-mount, now…

DOGE Plans to Rewrite Entire Social Security Codebase in Just ‘a Few Months’: Report

Details are scarce, but this has the potential to be a disaster.

President Donald Trump Pardons Ex-Nikola Boss Trevor Milton

Trevor Milton, who was sentenced to four years in prison last year for deceptively overselling…

The Woman in the Yard Is Terrifying, in a Very Uneven, Upsetting Way

Danielle Deadwyler stars in the new film from director Jaume Collet-Serra and producer Jason Blum.

HomeKit Weekly: Smartwings expands HomeKit blinds with PoE-powered Matter-over-Ethernet

Smart home automation is all about convenience or security. For me, automation with motorized shades…

The 2024 BMW XM Is Deeply Discounted But Still Ridiculously Expensive

How a car looks has no tangible impact on how it drives or performs, but…