Charles Friswell’s unique take on selling cars caused much confusion, and eventually led to him to get a knighthood

“Why does the Baby Peugeot? That’s silly, isn’t it? But it does.”

“SUCCESS, SUCCEEDS, SUCCESS: try and say that quickly six times and then say BABY PEUGEOT.”

“You don’t mind me being here, do you?” “BABY PEUGEOT has no infantile complaints.” “The car that will take any pill.” “Baby Peugeots won’t wash clothes, but every agent sells them.” “I have recently taken to motoring. I find it most fascinating.” “Why? Why Not?” “Who called me BABY PUGDOG?”

If you’re feeling bewildered by these impenetrably abstract slogans, consider how they looked amid the turgid and stiff-collared usual fare of early-1900s Autocar advertising in which they existed.

Enjoy full acccess to the complete Autocar archive at themagazineshop.com

Just what was going on? “PEOPLE SAY: FRISWELL’S advertisements ARE ABSURD. So do we; but if they were not you would not read them.”

Well, that explains that. How fabulously anachronistic, though – like some zoomer-baiting online marketing campaign 120 years early.

Even more so when you see the accompanying back-page imagery of Charles Friswell himself pulling silly poses or holding said voiturette in his palm, and indeed contrasted by such dry marketing copy as: “In response to continual demands for British-made tyres for heavy motor cars, of the excellence of Dunlop Tyres, arrangements are now being completed for the home manufacture of motor tyres for heavy vehicles.”

Friswell even ran an amusing illustration of the Baby Peugeot looping the loop on a rollercoaster track along with the slogan: “Photography cannot lie.”

He boasted of being Britain’s “only successful motor carriage auctioneer” in these earliest years of motoring (“he sells 90% more than any other firm advertising the same business”). It’s telling that his father was an advertising agent.

Having become involved with the new British invention of the safety bicycle, Friswell in 1896 got into the import and sale of another exciting new thing – the car – from France. Within a few years, he had opened Friswell’s Automobile Palace, a vast five-storey showroom at Holborn Viaduct in his native London.

It housed a vast storage area; a paint shop sufficient for 50 cars; an even larger repair shop; “the largest showroom in the world” for new cars; a motorcycle department; a garage for 200 cars; another for more than 100 carriages; rooms for weekly auctions; an electric charging and lighting station; a repository of 1030 safes; and a seven-ton lift. All furnace- heated, electrically lit and supposedly fireproof, too.

Friswell – still in his early thirties – probably wasn’t wrong when he called it the world’s largest motor depot. And that’s not to mention his firm’s two used sales depots at Holland Park and Long Acre.

As for the Baby, this was a nickname for two models.

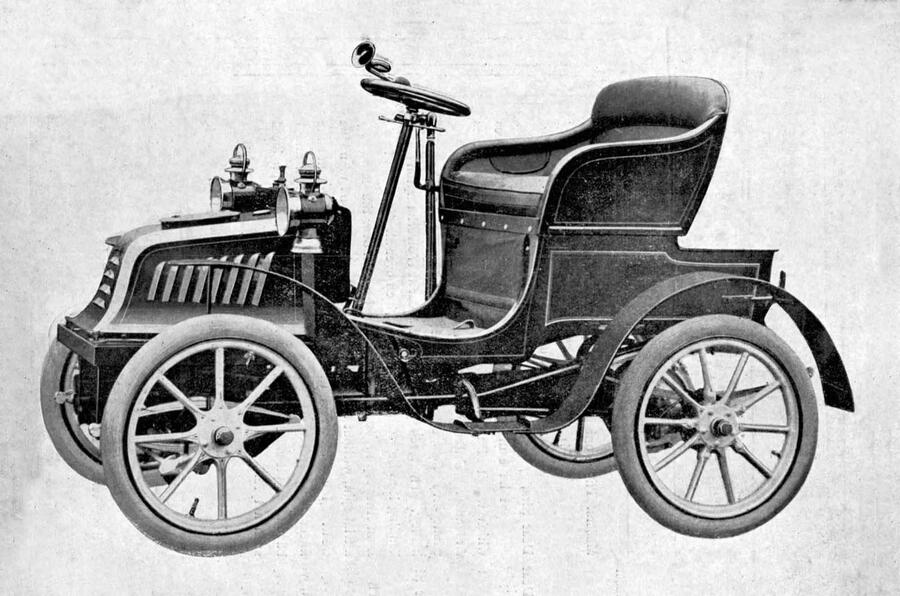

In 1902, the Type 37 was introduced by Peugeot – already long established in other areas of manufacturing – with a 5bhp one-cylinder engine, rear-wheel drive, permanently meshed gears and two seats.

“A useful little carriage for everybody. Useful for the gentleman who has a large car to run about on. Useful to the man who can’t afford to pay fancy prices. Any lady can drive it,” proclaimed Friswell.

Sochaux got more serious about car making in 1903 with the Type 54, similar in its mechanicals and design but upgraded to a V-twin. “Reliability, hill-climbing, horse-power, steering, consumption and vibration is where it excels,” said Friswell.

“Not how cheap but – How reliable. How economical. What power. Cheap enough with all these qualities: £175 [about £18k today].

“Once a Peugeot rider, always a Peugeot rider. Not flying machines, not racers, not marvellous – simply good machines.”

During this time, Friswell also won a famous case against a firm that claimed a patent entitled it to a 5% royalty on every car using a carburettor; he then became chair of car maker Standard; and in 1909 he was knighted, having provided for free cars to the Imperial Press Conference and motoring lessons to horse-drawn cab drivers who had lost their jobs to mechanisation.

Friswell died in 1926, aged 54. His dealership business had sadly gone under, presumably due to the disruption of the Great War, in 1915.

Source: Autocar RSS Feed